Thoughts about Lasso Regression

I’ve been thinking about Lasso regression lately, and more specifically, about regularization. I wanted to see if there was a way to reformulate Lasso regularization as a quadratic convex problem. The answer seems to be, ‘yes, but at what cost?’ (pun only intended in hindsight).

A Simple Observation

I’ve never been fond of the absolute value function. I prefer thinking about it as $\vert w\vert=\sqrt{w^2}$. This transformation made me wonder, can we write a function that minimizes at $\sqrt{w^2}$? There are many possibilities, but today, let’s focus on this:

\[\Lambda(s,w)=\frac{1}{2}\left(s w^2+\frac{1}{s}\right).\]Given that the domain is restricted to $s>0$, we have $\min_{s>0}\Lambda=\vert w\vert$. Why is this interesting? Because it’s a quadratic function in $w$. So, what does this have to do with Lasso regression?

Recall that in Lasso regression, we add the $L_1$ norm of the weights to the loss function. Specifically, if the unregulated loss function is $\ell(w)$, then the Lasso loss function is

\[\ell_{\rm lasso}(\boldsymbol{w})=\ell(\boldsymbol{w})+\lambda\Vert \boldsymbol{w}\Vert_1=\ell(\boldsymbol{w})+\sum_i\lambda\vert w_i\vert.\]Our brief discussion about the $\Lambda$ function leads us to understand that the Lasso regression can also be written as

\[\ell_{\rm lasso}(\boldsymbol{w},\boldsymbol{s})=\ell(\boldsymbol{w})+\frac{\lambda}{2}\left[\boldsymbol{w}^T{\rm diag}[\boldsymbol{s}]\boldsymbol{w}+\sum_{i}s_i^{-1}\right],\]where $\boldsymbol{s}$ is a vector of Lagrange multipliers, of the same dimension as $\boldsymbol{w}$. Effectively, we have doubled the weight space. So, what’s the benefit? The dependence on $\boldsymbol{w}$ is now quadratic, and the gradients with respect to both $\boldsymbol{w}$ and $\boldsymbol{s}$ are straightforward.

\[\boldsymbol{\nabla}_{\boldsymbol{w}}\ell_{\rm lasso}=\boldsymbol{\nabla}_{\boldsymbol{w}}\ell+\lambda\,{\rm diag}[\boldsymbol{s}]\boldsymbol{w}\;\;,\;\;\frac{\partial\ell_{\rm lasso}}{\partial s_i}=w_i^2-s_i^{-2}\]Keeping in mind that $s_i>0$, it is also clear that $\ell_{\rm lasso}$ is convex, given that $\ell$ is. Note that to circumvent the $s>0$ restriction, we may define $s=e^\sigma$. Minimizing $\ell_{\rm lasso}(\boldsymbol{w},\exp\boldsymbol{\sigma})$ with respect to $\boldsymbol{\sigma}$ over the reals will also give the desired $L_1$ regulator.

The Simplest Example Possible - 1D Linear Regression

To illustrate what we might achieve with this new perspective, let’s consider a 1D linear Lasso regression, where our model has only one parameter, say $y=w x$. The loss function would be

\[\ell=\frac{1}{2}\Vert w\boldsymbol{x}-\boldsymbol{y}\Vert_2+\frac{\lambda}{2s}(s^2w^2+1).\]The derivatives for $w$ is given by

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial w}=w(x^2+\lambda s)-\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{y}\;\;\Rightarrow\;\;w=\frac{\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{y}}{x^2+\lambda s}.\]Given that both $s$ and $\lambda$ are positive, we see that the regularization pushes the weights towards smaller values. Now, moving to the $s$ equation,

\[\frac{\partial \ell}{\partial s}=\frac{\lambda}{2}(w^2-s^{-2})\;\;\Rightarrow\;\;s^2=w^{-2}=\frac{(x^2+\lambda s)^2}{(\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{y})^2}.\]We can combine the two equations above into a single equation for $w$,

\[\boxed{w=\frac{\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{y}}{x^2+\lambda\vert w\vert^{-1}}}.\]Instead of solving this equation directly, I suggest viewing this as an iterative process. This implies the existence of a sequence of $w$ values, $w^{(i)}$, $i=1,2,…$ such that

\[w^{(i+1)}=\frac{\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{y}}{x^2+\lambda\vert w^{(i)}\vert^{-1}}.\]The convexity of the loss function assures the convergence of this process. By further setting $w^{(0)}=1$, the first iteration ($w^{(1)}$) gives the Ridge regression result. This insight allows us to interpret Lasso regression as a sequence of modified Ridge regression problems, as we next study in more depth.

Lasso Regression as a Sequence of Ridge regression Problems

Building on the simplified discussion above, I propose treating Lasso regression as a sequence of modified Ridge regression problems, expressed as

\[\ell^{(i)}\left(\boldsymbol{w},\boldsymbol{w}^{(i-1)}\right)=\ell(\boldsymbol{w})+\frac{\lambda}{2}\boldsymbol{w}^TD[\boldsymbol{w}^{(i-1)}]\boldsymbol{w}\;\;,\;\;D[\boldsymbol{w}]={\rm diag}\left[\vert w_1\vert^{-1} ,\vert w_2\vert^{-1} ,...,\vert w_N\vert^{-1} \right]\]with $\boldsymbol{w}^{(0)}=\mathbb{1}$, and $\boldsymbol{w}^{(i>0)}$ are the weights minimizing $\ell^{(i)}$. Repeating this iteratively, will eventually converge to the same minimum as the Lasso regression.

The Next Simplest Example Possible - linear regression

To further illustrate this approach, let’s examine a regularized linear regression problem. In this case, we have

\[\ell^{(i)}=\frac{1}{2N}\Vert X\boldsymbol{w}-\boldsymbol{y}\Vert_2+\frac{\lambda}{2}\boldsymbol{w}^TD^{(i-1)}\boldsymbol{w},\]where $N$ is the number of samples. The normal equations are simply

\[\left(X^TX+\lambda ND^{(i-1)}\right)\boldsymbol{w}^{(i)}=X^T\boldsymbol{y}\;\;,\;\; D^{(0)}=\mathbb{I}.\]In the near future, I will follow up on this post with a more detailed discussion of numerically implementing this method in some more sophisticated settings, where analytical solutions can’t get us far. But for the time being, to investigate this numerically, I have set up a simple Python experiment using the California Housing dataset from Scikit-learn. I applied the Lasso sequence Ridge function for a specific $\lambda$, and tracked the evolution of each weight over iterations. The full Python notebook is available on GitHub, but the code snippet below provides an overview of the method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

def lasso_sequence_ridge(X, y, lambda_, num_iterations):

n_samples, N = X.shape # the number of features and samples

w = np.ones(N) # initialize the weights

w_history = [] # list to store the history of weights

# scale the lambda by the number of samples

lambda_scaled = lambda_ * n_samples

for i in range(num_iterations):

D = np.diag(1/np.abs(w)) # diagonal matrix of absolute weights

# solve the normal equations

w = np.linalg.inv(X.T @ X + lambda_scaled * D) @ X.T @ y

w_history.append(w)

return np.array(w_history)

Setting $\lambda=0.1$, we compared the obtained weights to those from the standard Lasso regression as implemented in scikit-learn. The weights from our sequence of Ridge regressions converged to values very similar to those from the Lasso regression, validating our approach.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

lasso = Lasso(alpha=lambda_)

lasso.fit(X, y)

print("Final weights from Lasso:")

print([f'{x:.3f}' for x in lasso.coef_])

print("Final weights from sequence of Ridge regressions:")

print([f'{x:.3f}' for x in w_history[-1]])

The output is

1

2

3

4

Final weights from Lasso:

['0.706', '0.106', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.011', '-0.000']

Final weights from sequence of Ridge regressions:

['0.706', '0.106', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.000', '-0.013', '-0.000']

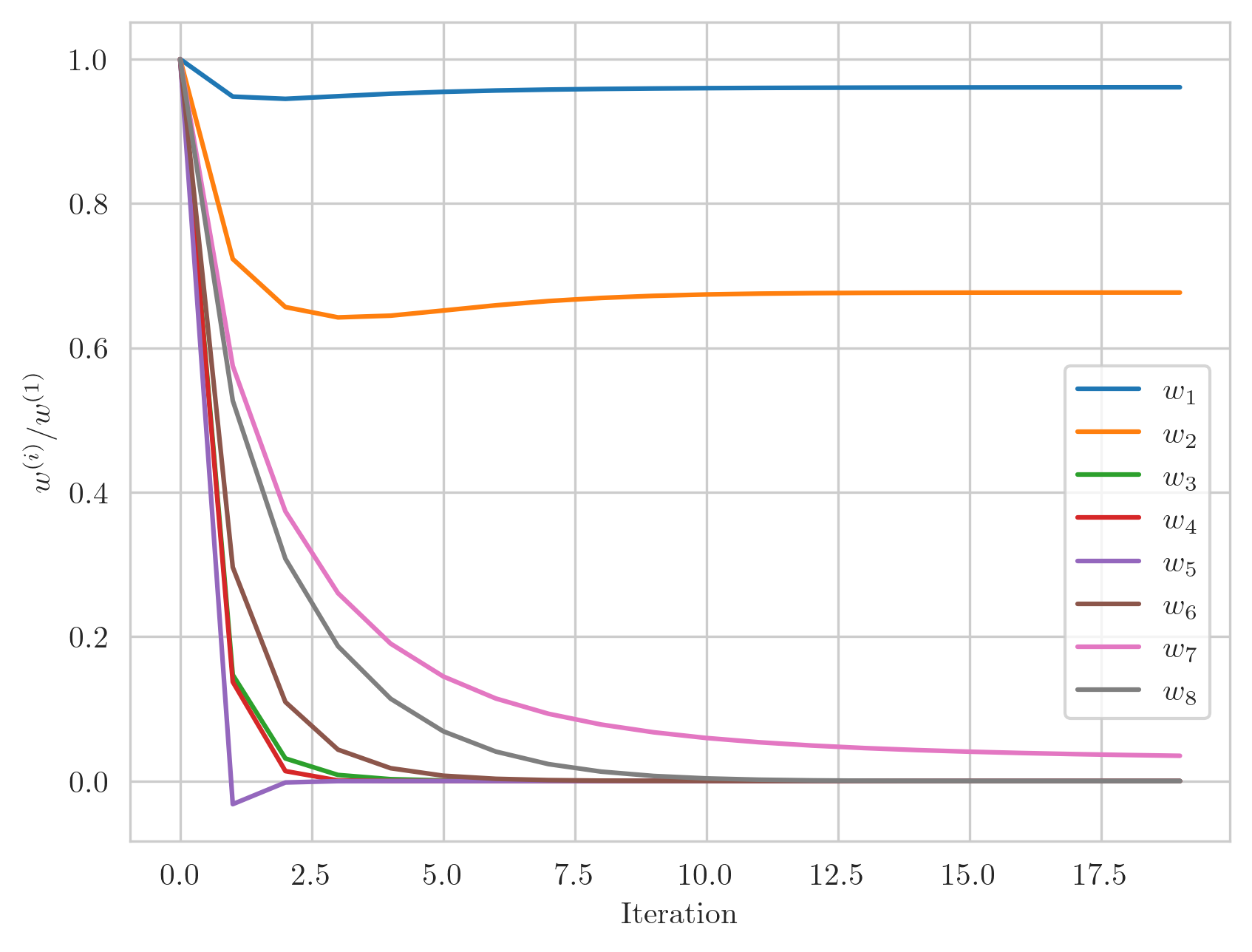

The plot below visualizes how each weight in the model evolves over the course of iterations, starting from the initial Ridge-like weights and converging towards their final values.

Convergence of the weights in Lasso regression as a sequence of Ridge regression problems. Each curve represents the evolution of a single weight parameter normalized by its initial value. Notice how all curves eventually converge to their final values, demonstrating the process of gradual ‘feature selection’.

Convergence of the weights in Lasso regression as a sequence of Ridge regression problems. Each curve represents the evolution of a single weight parameter normalized by its initial value. Notice how all curves eventually converge to their final values, demonstrating the process of gradual ‘feature selection’.